By Pat McKee

My friends and colleagues know me mostly as a philosopher. It surprises some of them that I also spend substantial time in the art of painting. I admit that this combination of interests is a bit unusual. But it is perfectly natural. After all, both philosophers and painters have a basic concern with the difference between appearance and reality. They share the goal of helping us see through the “pasteboard mask”of appearance to a metaphysical reality behind it. What surprises me is not that a philosopher would be interested in painting, but rather how infrequently philosophers collaborate with painters.

Why do philosophers so often overlook what they have in common with painters? I have come to think it is because philosophers, like the public in general, incline to a view that the best way to understand a work of art is through causal, or scientific, rather than through philosophical, explication.

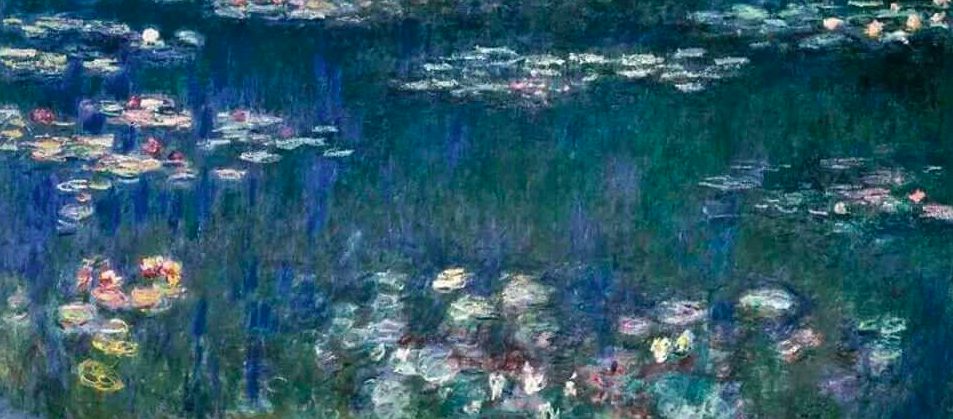

I felt validated in this view when I recently participated in conference dedicated to discussion of the last paintings of the famous impressionist, Claude Monet. These are the giant lily pad images that cover whole walls in the Musée de l`Orangerie in Paris. Besides being unusually large, the paintings have a distinctive roughness of execution, in which some areas of the canvas are left uncovered, and many areas show only abstract sketching, with no clear edges to mark where one thing begins and another ends. The colors are also unusual for Monet, grayed-down and dark compared to the sun-drenched bright hues of his earlier impressionism.

What struck me in the discussion was how quickly a consensus formed around the statement that Monet had adopted the larger format, undefined edges, darker colors, etc. because he had lost a measure of his vision due to cataracts. I found this explanation unsatisfying, because while it correctly identifies the causal condition of the paintings’ execution, it gives no insight into them as paintings. After all, we could cite the same limited vision to explain how Monet chopped wood or folded his clothes. To understand the works as paintings, we need to know what Monet was trying to say with them, bearing in mind that, while his eyes had been changed, they were still the eyes of an artist. To understand the paintings as paintings, we need to know what Monet found in the scenes he was seeing, with admittedly altered eyesight, that nevertheless served his effort to separate appearance and metaphysical reality.

For this we must turn to the main philosophical concepts apt for articulating the meanings in art works; the beautiful and the sublime. For the difference between Monet’s earlier works and these late paintings is that they mark a shift in his philosophy of art. That shift consists in a move away from the world as beautiful, with the bright, sunny colors and harmonized lines and shapes of early impressionist painting, to an aesthetic interest in the darker, relatively inchoate aspects of the world and its boundless, awe-inspiring size. In short, Monet’s last paintings mark a shift from a concern with the world’s beauty to a concern with its sublime aspects. To understand this is to understand the paintings on the level of their meaning, going beyond their philosophically less interesting causal history.

But what is “the sublime,” and where specifically do we see it in Monet’s last paintings? According to Immanuel Kant, the sublime is the aspect of immensity we sometimes perceive in things that that makes us feel awe. One of his examples is our aesthetic perception and contemplation of the starry night sky, the “heavenly vault.” Its boundless immensity makes us feel small, insignificant. We feel vaguely threatened by the thought of being lost in a universe of infinite darkness. Also, darkness renders all things relatively formless to perception, robs them of clear boundaries and definite position, and this, too, makes us feel a vaguely threatened by an implied loss of control over them.

But then, Kant says, the very same perceptual contemplation surprisingly awakens in us a sense of our own inner ability to overmatch that threatening immensity and dark formlessness with an equally awesome power of moral independence from the physical limitations that were just imposing a painful awareness of our vulnerability and limits. Even as we recognize the world’s physical domination of us, we simultaneously achieve an awareness of our own transcending “supersensible” powers to resist and transcend spiritual defeat by that fact. This aspect of aesthetic perception intimates, Kant says, a distinctively philosophical insight into our nature as free and rational agents and of our place (our “vocation”) in the universe.

Three features of Monet’s paintings may be cited as embodying the sublime as Kant represents it. First, their imposing size. They reach from floor to ceiling – a full eight feet high. But even more important, they stretch from one end of a long room to the other. Standing at one end of the painting, looking down its horizontal length, the space represented behaves like the night sky; it stretches into a distance without visible boundary or definable limit. Second, the rough execution of shapes in the paintings gives those shapes an absence of edge, leaving them with the formlessness which Kant cited as a primary marker of the sublime. Finally, the relative darkness of the paintings also brings an element of sublimity into our contemplation of them.

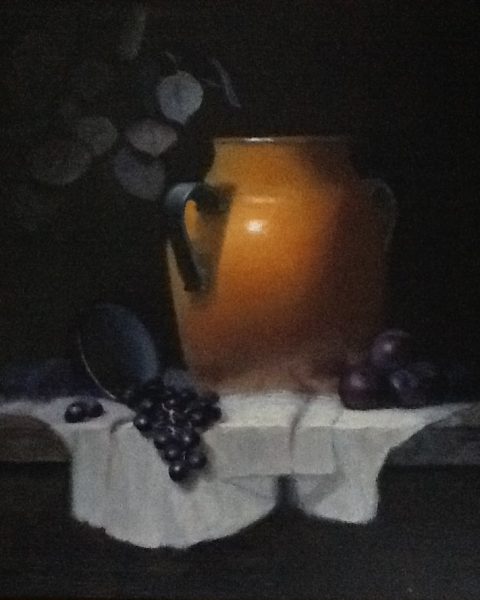

Monet’s capture of the sublime in his late works shows that paintings can embody and communicate philosophical meanings. Back in my own studio, I work to capture something of the metaphysical sublime in my own paintings. In the paintings you see here, I express the sublime by invoking the intimidating mystery of darkness, answered dialectically by a counter- affirmation of color and light. For me, creating such images blends seamlessly with verbally articulated philosophical reflections.